Survive, Evade, Resist, Escape: Bringing SERE Principles into Everyday Flying

- The Thrifty Pilot

- Aug 2, 2025

- 20 min read

Imagine you’re out on a routine cross-country flight in your Cessna when an engine failure forces you into an unexpected off-airport landing. The good news: you walked away. The bad news: you’re now stranded in unfamiliar terrain, and help might be hours (or even days) away. What you do before and after this kind of emergency can mean the difference between a story with a safe ending and a dire outcome. This scenario is where the core principles of SERE,which stands for Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape,come into play. SERE is a concept originally developed for military pilots to survive behind enemy lines, but its lessons extend far beyond combat. In fact, every general aviation pilot can benefit from SERE’s focus on preparation, mindset, and resilience. As a crisis and emergency management professional (and fellow pilot), I’ve seen first-hand how being prepared and staying calm under pressure saves lives. In this post, we’ll explore how you can apply SERE principles in day-to-day flying, trip planning, and your overall pilot mindset,all in The Thrifty Pilot’s practical, grounded style.

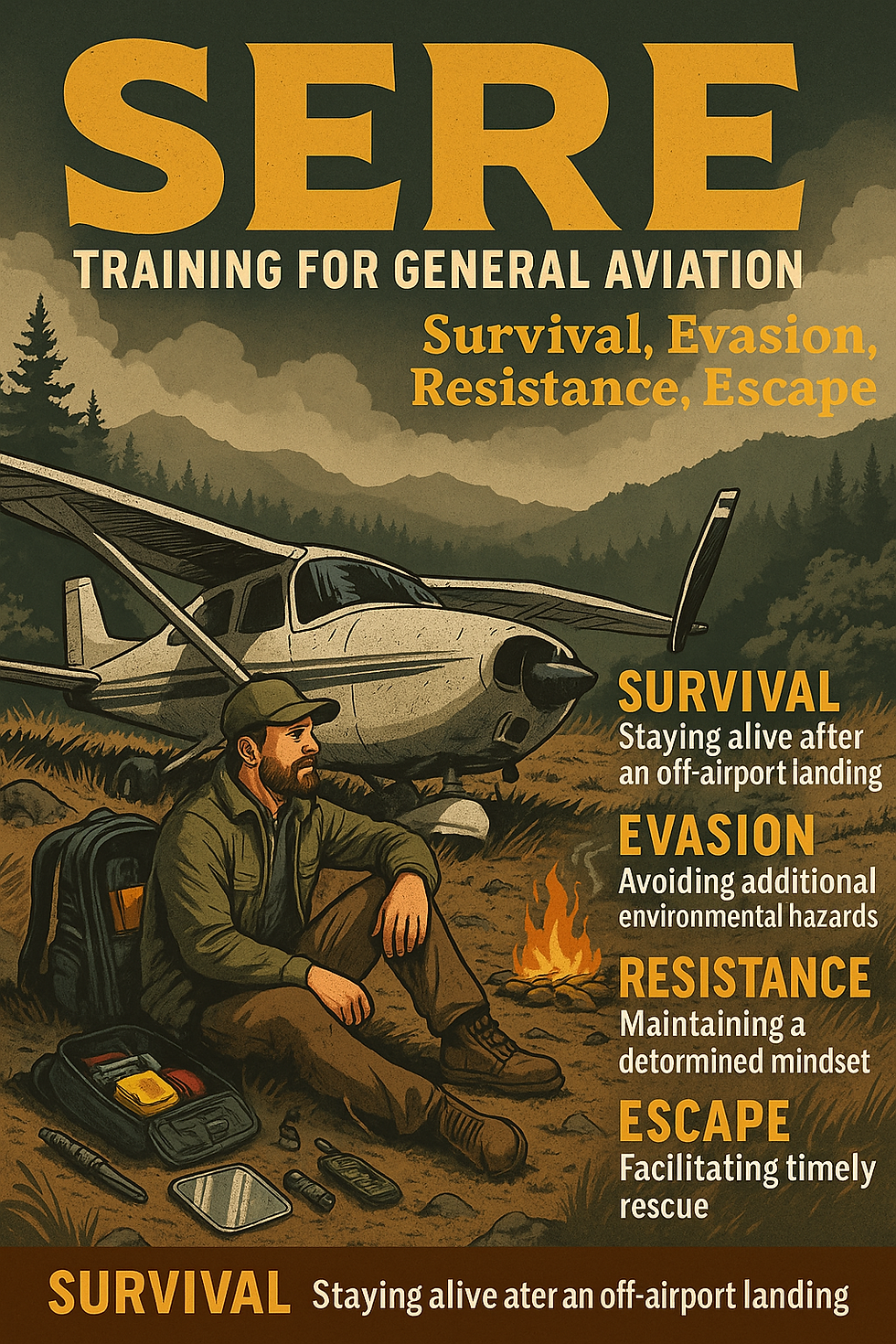

What is SERE and Why Should Pilots Care?

Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape (SERE) is best known as a military training program to help aircrew survive if they are shot down or isolated. Now, as a civilian pilot you’re not worried about enemy capture,but you do face other threats like mechanical failures, extreme weather, or getting lost in remote areas. SERE’s core idea is preparedness: having the skills, gear, and mental fortitude to handle whatever situation is thrown at you. The four pillars of SERE can be translated into everyday flying as follows:

Survival: Staying alive after an accident or forced landing,through first aid, shelter, fire, water, and signaling for help.

Evasion: Avoiding or minimizing further hazards,whether it’s steering clear of bad weather in flight or finding safe shelter and avoiding environmental dangers on the ground.

Resistance: Maintaining mental resilience,resisting panic, fatigue, or hopelessness; staying disciplined and focused on survival tasks.

Escape: Getting out of the emergency,from quickly extricating yourself from a downed aircraft, to facilitating rescue (being found and returned to safety).

Adapting SERE doesn’t mean turning into a Rambo or carrying a machete in your flight bag. It’s about adopting a practical mindset of preparedness. Even professional backcountry flying courses incorporate SERE-based survival training for civilian pilots. And you don’t need a military budget either,affordable, resourceful measures can dramatically improve your odds in an emergency. In the next sections, we’ll break down each SERE component with realistic, pilot-friendly tips.

(Spoiler alert: None of this is about eating bugs or building jungle snares. It’s about smart planning, having the right gear, and the mindset to handle adversity.)

Survival: Prepare for the Unexpected

“The best time to prepare for an emergency is before it happens.” This saying holds true in aviation just as it does in crisis management. Survival starts well before you ever take off. It begins with acknowledging that accidents can happen to anyone,including you. A FAA survival instructor put it plainly: the first step is admitting “It Can Happen To Me.” That mindset shift alone will motivate you to take survival preparation seriously, rather than assuming “nah, I’ll never need that stuff.”

One eye-opening case: a simple flight over flat, populated Florida ended in a crash that wasn’t found for six months, even though the wreck was only a few miles from the airport and a few hundred yards from a road. The pilot hadn’t left a flight plan or clear route info, so nobody knew where to look. Stories like this make it clear: if you ever face a forced landing, you might be on your own for longer than you think. Being equipped and ready is essential.

Survival preparation for pilots comes down to two main areas: equipment (gear) and knowledge (skills/techniques). Let’s start with gear,your survival kit.

Example of a compact aviation survival kit with affordable essentials: a multitool, fire starter, wire saw, signal mirror, emergency blanket, first aid basics, and more. Building your own kit can be budget-friendly and potentially life-saving.

Carry a Survival Kit (and Know How to Use It). Every pilot should have at least a basic emergency kit in the aircraft. In fact, everyone,whether flying around the pattern or across the country,is encouraged to have a survival kit on board and know how to use it. You can buy pre-made aviation survival kits, but assembling your own is often cheaper and lets you customize contents to your needs (the Thrifty Pilot way!). Here’s a checklist of useful survival items that won’t break the bank:

First Aid Kit: Include bandages, gauze, antiseptic wipes, pain relievers, any personal medications, and some trauma items (tourniquet, clotting gauze) if possible. You can find compact kits for ~$50 or build one yourself. Tip: Many pilots keep a larger survival-oriented first aid kit in the plane and a smaller one in their flight bag.

Fire and Shelter: Pack a fire starter (waterproof matches or a ferro rod and a lighter) and tinder (e.g. cotton balls with petroleum jelly). Add an emergency space blanket or bivvy sack (these foil-like blankets cost under $5) and/or a lightweight tarp or poncho. Staying warm and dry is critical if you’re spending a night outside, especially in cold or wet conditions.

Water and Food: Stash a water bottle or pouch (at least a liter) plus water purification tablets or a filter straw (like a LifeStraw ~$20). Hydration is far more important than food in the first 24-48 hours. Still, throwing in a few energy bars or packs of nuts is wise for morale and calories.

Signaling Devices: Include at least a loud whistle (a $5 item that can carry farther than your voice), a signal mirror (for attracting attention from search aircraft), and a high-visibility cloth or vest. If space allows, a flare or smoke signal and a battery-powered strobe light are great for nighttime signaling. Modern tech bonus: a personal locator beacon (PLB) or satellite messenger (SPOT/InReach) can send SOS signals with GPS coords,these devices cost a few hundred dollars, but even a basic 406 MHz PLB drastically increases your chances of rescue. (It’s literally a life-saver; for roughly the cost of a tank of avgas, a PLB is worth it).

Tools and Miscellany: A quality knife or multitool is indispensable (you can get a decent multitool ~$30). Pack some 550 paracord (versatile rope), a small LED flashlight or headlamp (with spare batteries), and perhaps a compact compass. Other handy items: duct tape (wrap a few feet around a pencil), gloves, a bandana (for sun protection or bandage/sling use), and bug repellent in summer. If flying in winter or mountainous areas, add hand warmers and maybe a wool cap. In desert areas, include sunscreen and an extra water reserve. Tailor your kit to your typical flying environment.

Remember, any survival kit is only as good as your ability to access and use it. Keep the kit within reach or on your person. It won’t help you if it’s buried in the baggage compartment under heavy gear. Many pilots like to put critical items in a fishing vest or photographer’s vest worn while flying,that way, even if you have to evacuate in a hurry, you leave with the essentials on you. As the FAA’s guidance notes, your personal survival kit must be “readily and easily accessible in the event of an emergency evacuation”.

Now, beyond gear, survival training and knowledge are the other half of the equation. You don’t need to attend a military SERE school, but consider taking a one-day aviation survival course if offered in your area (sometimes local FAA Safety Team or pilot groups host them). At minimum, read up on survival basics for the regions you fly over,e.g. wilderness survival tactics for forested areas, or desert survival tips if you’re in the Southwest. Knowing how to build a fire, erect a quick shelter, or treat a serious injury in the field are skills you hope you never need, but if you do need them, you’ll need them desperately. One Air Force survival instructor was once asked, “What’s the most important piece of survival equipment?” His answer: “You.” In other words, your knowledge, attitude, and decision-making are the ultimate tools.

Finally, survive the crash itself. This may sound obvious, but it’s worth noting: investing in a few safety upgrades and habits can dramatically improve your odds of surviving an accident so you get the chance to put your survival kit to use. The FAA found that in places like Alaska, simply using proper restraints (adding four- or five-point harnesses) and wearing helmets could save 60% of lives in crashes. So, if you fly a vintage plane with only lap belts, consider adding shoulder belts or a full harness. If you do a lot of backcountry or off-airport flying, a helmet might be a worthwhile addition. Even on a budget, at least wear proper clothing when you fly: sturdy shoes (not flip-flops or dress loafers), and weather-appropriate layers. If you’re forced down in rough terrain, you may need to walk out or spend a cold night outside. Don’t be that pilot who crashes in the mountains wearing shorts and sandals. Dress for survival just in case,as the saying goes, “dress to egress.” Having a jacket, hat, and gloves within reach in winter can be a literal lifesaver.

Bottom line: Hope for the best, plan for the worst. Pack the gear and knowledge to survive an emergency, even if it’s uncomfortable to imagine. As pilots, we hope we never have to unzip that survival kit. But as prepared pilots, we carry it anyway,for our passengers, our families, and ourselves.

Evasion: Avoiding Trouble in the First Place (and After)

In SERE training, “evasion” is about avoiding capture or further danger after bailing out. For everyday pilots, think of evasion as avoiding the situation from ever getting that bad,and if it does, minimizing additional risks. This principle is all about situational awareness, smart planning, and quick action to sidestep trouble.

1. Evasion in Flight,Stay Ahead of Emergencies. The best way to survive an emergency is to not have one! While not all problems can be prevented, a large number of accidents come from pilots pressing on into deteriorating situations. “Evasion” in this context means avoiding hazardous conditions and poor decisions:

Plan and monitor your route with safety in mind. Before takeoff, plan your flight with “outs”. Identify alternate airports along (or slightly off) your route, and note terrain and major roads. If crossing large remote areas, consider flying slightly longer routes that keep you within reach of landing spots. For example, follow valleys instead of going direct over high peaks, or track near highways rather than over unbroken forest. Know what roads or towns are along your path and what direction to head to reach them. This way, if you do go down, you have a better sense of where the nearest help could be,and rescuers have a better chance of finding you. (I always carry a state sectional or map in the cockpit, and I mentally note, “Okay, the interstate is 10 miles east of me” during cruise.)

Keep an eye on fuel and weather,and don’t hesitate to divert. Situational awareness means continuously evaluating your fuel status, weather, and aircraft condition. If you’re getting close to minimum fuel, land while you still have options. If weather is worsening, turn around or divert before you’re stuck scud-running. Avoiding fuel exhaustion or VFR-into-IMC already means you’ve evaded two of general aviation’s biggest killers. This is where resisting “get-there-itis” overlaps with evasion,more on that in the Resistance section.

Always have an emergency landing site in mind. A great habit taught in primary training is to constantly ask yourself, “If the engine quit right now, where would I land?” As you cruise along, scan for fields, roads, sandbars,anywhere you could put down relatively safely. Your options change by the mile, so keep updating your plan. This mindset keeps you sharp and ensures that if the worst happens, you’re not completely out of ideas. It’s a form of mental evasion: you’re preemptively evading a crash in unforgiving terrain by always having a plan to glide to something better. Pilots who practice this find that in a real engine-out, they lose less time to indecision because they already know where to turn.

2. Evasion on the Ground,Don’t Make Things Worse. If you do find yourself on the ground after an emergency landing, “evasion” means avoiding any further harm while awaiting rescue:

First, take care of immediate dangers. After a crash, evacuate and move a safe distance away from the aircraft if there’s any risk of fire or explosion. As the FAA recommends, within the first few minutes you should get everyone out, check for injuries, and activate emergency signals. If you smell fuel, create distance and have a fire extinguisher ready if you carry one. In some cases, staying near the aircraft is wise (it’s a big, visible signal for searchers), but not if the aircraft poses a threat (leaking fuel, in the path of wildfire, etc.).

Shelter from the elements. Once the scene is stable, address exposure risks. If it’s cold, wind, or wet, evade hypothermia by getting a shelter set up or at least huddling in a protected area. Use that emergency blanket or a makeshift lean-to with your tarp or even the aircraft’s wings and a tarp/poncho. If it’s a desert afternoon, evade heatstroke by finding shade (even if that means rigging a wing or parachute as a sunshade) and avoiding strenuous activity in the heat of the day. In survival, nature can be an adversary; your job is to evade its worst effects.

Don’t wander off without a plan. One of the hardest decisions in a survival situation is whether to stay with the aircraft or attempt to hike out. In most cases, especially if you’ve filed a flight plan or people know to look for you, staying put near the aircraft is recommended. The airplane wreckage is a large signal for rescuers and provides some resources (shelter materials, radio, etc.). Wandering randomly can make you harder to find and could lead to getting more lost or injured. Only consider leaving if you are certain no one knows you’re missing (no flight plan, no radio call, overdue not noticed) and you have a clear idea where civilization is (e.g., you overflew a road a few miles back). Even then, proceed with caution: leave a note at the aircraft with time, direction of travel, your names, etc., and use your compass/GPS to walk in a deliberate direction (following a drainage downhill, or toward a known highway). Evasion here means avoiding becoming a “missing” moving target. In emergency management we often say: don’t turn an emergency into a worse emergency. Sometimes staying put is the most prudent form of evasion.

Wildlife and other threats. In North America, encounters with dangerous wildlife are rare, but use common sense. Keep food sealed and away from your shelter to avoid attracting critters. Know the basics: in bear country, for example, it’s wise to make noise so you don’t startle any animals. If you have a fire, it will usually keep animals at bay. Insect swarms (mosquitoes, etc.) can be not only annoying but disease-carrying,use that bug repellent from your kit. Essentially, evasion = steer clear of new problems while you deal with the big one.

3. Evasion as Risk Management (Mindset). On a philosophical level, evasion is about anticipation. In your pre-flight planning and day-to-day flying, cultivate a habit of asking “What if…?” and then mitigating the risk. What if the weather along my route is worse than forecast,do I have enough fuel to turn around or divert? What if I lose my alternator at night,do I have a flashlight and minimal electrical load plan? What if I have an engine fire on takeoff,do I have a briefed plan to get on the ground immediately? This isn’t paranoia; it’s preparedness. Professional pilots and military aviators use scenario planning to evade being caught off-guard. You can do it too, informally: a quick chair-flying of “If X happens now, I’ll do Y.” This practice builds confidence and muscle memory that help you act decisively when seconds count. As one Air Safety Institute publication put it, “worst-case preparation matters”,the choices you make before takeoff (route, gear, briefings) hugely influence the outcome of an emergency.

In short, Evasion = Proactive Safety. It’s far better to avoid a survival situation altogether by managing risk in flight. And if you end up in one, it’s about avoiding any further harm. Remember, as a pilot you’re the leader in an emergency,guide yourself and your passengers away from danger and towards safety.

Resistance: The Will to Survive (Mental Resilience)

Survival isn’t just about tools and techniques,it’s about mental attitude. In fact, many survival experts say that survival is “90% mental and 10% physical”. The “Resistance” component of SERE, in a military sense, refers to resisting enemy exploitation. For us, it means resisting fear, panic, and the natural human tendency to give up hope. It’s about cultivating a mindset of determination and discipline that will carry you through an emergency.

Cultivate the Will to Survive: The single most important factor in any survival situation is the will to survive. History and research are full of stories where individuals survived incredible ordeals largely because they refused to quit. After a 2024 crash in frigid water near Rhode Island, a Civil Air Patrol pilot credited her survival to the mindset she learned in training,she literally thought, “I’m not going to die today.” That fierce resolve kept her fighting to stay alive until rescue. As the FAA’s survival training materials put it, “Without a ‘will to survive,’ there can be no survival. If you do not have a desire to survive, no equipment will help you.”

So how do you strengthen your will to survive? Start by visualizing success. This might sound a bit touchy-feely, but it works. In any emergency (aviation or otherwise), tell yourself: “I can handle this. I will get through this.” This positive self-talk actually helps blunt panic. In crisis management, we train people to replace “I’m going to die” with concrete tasks: “I need to do X, then Y.” Focus on the next step rather than the big picture of dread.

Use Checklists and Training to Resist Panic: As a pilot, you’re used to following checklists and procedures,lean on that habit in an emergency. Aviate, navigate, communicate… and then, survive. If you’ve practiced emergency landings, you’ll resist the knee-jerk freeze-up when the engine goes quiet. If you’ve mentally rehearsed unbuckling and evacuating, you’ll be less likely to freeze in shock after a crash. Good training “kicks in” when stress is sky-high. As AOPA’s Air Safety Institute notes, training and actions can determine your fate,good training generally yields better results in emergencies. In other words, prepare now so that you can resist panic later. Something as simple as yelling out your priorities (“Fire,get out now!” or “OK, everyone is alive, now we need shelter and to activate the ELT”) can snap you and others out of paralysis and into action. It imposes order on chaos.

Stay Positive and Stay Busy: A hallmark of survivors is that they maintain a positive mental attitude against the odds. The FAA survival manual states, “Having a positive outlook may be the difference between success and failure. A positive mental attitude will be tested by many factors… that test your will to survive.” This means actively resisting despair. One practical tip is to set small, achievable goals: “Let me make a shelter before sundown,” “Let me gather enough wood for a fire tonight,” etc. Each task you complete builds confidence and keeps your mind focused. In psychology this is known as gaining “micro-control”,small wins that bolster your morale. Conversely, avoid sitting idle and stewing in fear. Stay occupied with useful work or even sing/talk to yourself or others to keep spirits up.

Resist Pain and Discomfort: Survival situations are rarely comfortable. You might be injured, cold, or tired. While you must be mindful of injuries (treat what you can), a survivor’s mindset involves a degree of toughness,resisting the urge to collapse or panic at every ache. Remind yourself that pain is often temporary and can be overcome or managed. If you have passengers, project calm and confidence to “resist” the spread of panic. Your attitude is contagious. In emergency management we say, “Manage your emotions or they will manage you.” Take deep breaths, focus on facts (“We have a locator beacon activated, help is likely on the way, we just need to stay warm and hydrated until then”), and even use humor if appropriate to lighten the mood.

Resisting Temptations in Decision-Making: There’s another angle to “resistance” relevant to everyday flying: resisting hazardous temptations before an emergency happens. This is the discipline side of being a pilot. For example, resist the temptation to push your personal minimums. If you’re VFR-only and you see the weather deteriorating, resist that little voice saying “Maybe it’s not that bad, I’ll just continue.” Have the discipline to divert or turn back early. Resist get-there-itis when you’re behind schedule,better to arrive late (or drive) than not arrive at all. Likewise, resist external pressure from passengers or work. A SERE mindset applied to civilian flying means you stick to your plan and values under pressure, much as military personnel are taught to stick to their Code of Conduct. In practice: cancel or delay a flight if things aren’t right (yes, even if you’ve already rented the plane or promised someone a ride). Your safety comes first.

In summary, Resistance = Mental Grit and Discipline. It’s about being the pilot who stays cool in the cockpit during an emergency and the survivor who refuses to quit on the ground. You don’t have to be superhuman,you just have to prepare and decide, in advance, that you will face adversity with a “I’ve got this” attitude. When the time comes, that internal resolve will be your most powerful survival tool.

Escape: Getting Home Safe and Sound

The final piece of SERE is “Escape.” For a downed pilot in hostile territory, that means sneaking out or getting rescued without capture. For us in the civilian world, “escape” means getting rescued and returning to safety as efficiently as possible. After you’ve survived the immediate crash and stabilized the situation, your goal is to make it easy for search and rescue (SAR) teams to find you (or to self-rescue if necessary).

Help the Rescuers Find You: The moment you’re in a forced landing or emergency situation, think about how you will signal for help. Modern tech does a lot of this for us,your aircraft’s ELT (Emergency Locator Transmitter) will likely activate on impact. Newer 406 MHz ELTs transmit your location to satellites (and also broadcast on 121.5 for local homing). However, ELTs aren’t foolproof; some impacts don’t trigger them, and older models might not alert satellites. That’s why activating your own locator is crucial. As soon as you’re able, manually activate the ELT if it hasn’t already (many have a panel switch) and use a personal locator beacon (PLB) if you have one. The FAA advises: “Activate your ELT (and personal locator beacon if you have one), and use your phone to call 911” as soon as initial injuries are addressed. If you have cell signal, a 911 call (or even a text to 911) can dramatically speed up rescue,just be aware of your approximate coordinates from your GPS if you can.

Beyond electronic aids, use visual signals to attract attention. This is old-school but effective. In daylight, a signal mirror can catch the eye of search planes many miles away,aim it at any aircraft you hear or at the sun periodically (some mirrors have instructions to help aim; practice if you can). Brightly colored panels or clothing laid out on the ground in a large shape (e.g., a giant “X” or “SOS”) can be spotted from the air. At night, a fire is your best friend for signaling (and warmth). Three fires in a triangle is the international distress signal, but even one bonfire in a clearing sends a clear message. Use flares if you have them when you hear/see rescuers nearby. Whistles and shouts can help ground search teams locate you once they’re in range.

A key part of escape/rescue is communication,letting people know you’re in trouble and where you are. This starts before your flight: file a flight plan or leave a detailed itinerary with someone you trust. This simple step ensures that if you don’t show up, someone will raise the alarm and they’ll have a clue where to start looking. If you were receiving VFR flight following or had made any mayday calls, ATC will also have a last known position to give to SAR. (Bonus thrifty tip: utilizing free VFR flight following when available is like having an extra set of eyes that know your position,if you vanish, ATC knows roughly where to send help.)

If you find yourself considering self-rescue (escaping on your own), weigh the pros and cons carefully. As mentioned in Evasion, staying with the aircraft is often the best course. However, there are scenarios where you might need to move,for example, if you landed in an area without any hope of radio or cell contact and no one will know to look (no flight plan). In that case, “escape” might mean hiking out to the nearest town or vantage point to call for help. If you choose to do this, do it smart: travel during safe times (daylight if terrain is hazardous; or at night if in a desert to avoid heat), and leave signals along the way (arrows made of rocks or sticks, notes). This way, searchers arriving at your plane can tell which way you went. Never just walk out without leaving a trace or plan, or you risk turning a locate-able incident into a wilderness search-and-rescue needle-in-haystack.

Another form of escape is escaping the aircraft wreckage itself if it’s a dangerous environment. For instance, if you ditch in water, your escape skills (egress training, use of flotation devices) are critical. Do you know how to pop a door or window open so you’re not trapped by pressure? If you fly over water often, consider practicing water ditching procedures or taking a course. At minimum, carry inflatable life vests (and wear them when over water,a vest under your seat won’t help if you can’t grab it in time). Similarly, if a post-crash fire is a threat, your ability to unbuckle and get everyone out in seconds is vital. Brief your passengers on how to open doors or hatches, and who will grab the ELT or survival kit if time allows. This comes back to planning: as PIC, brief your passengers before flight that “in an emergency, follow my instructions, exit quickly, then meet at a safe spot 100 yards away” or whatever your plan is. It might seem overcautious during a sunny weekend jaunt, but if something goes wrong, their panic will be lower if they recall your instructions. AOPA’s safety advisors emphasize briefing everyone on where survival gear is and how to use it,it “can significantly influence the outcome of a crash in your favor”.

One more tool in escaping a bad situation is communication and navigation aids. If your aircraft radio still works after an off-field landing (say you landed gear-up in a field but avionics are fine on battery), you can attempt to contact any overflying aircraft on emergency frequency 121.5 (or use your handheld radio if you carry one as backup). A simple “Mayday, aircraft down [location if known]” might get relayed. Some pilots also carry portable ELT beacons or even personal satellite communicators which allow texting a family or friend. Use whatever means available to let the world know you need help.

The goal of “Escape” is to get you out of the wilderness and back to a warm bed as soon as possible. By stacking the odds in your favor,filing that flight plan, carrying that PLB, knowing your signaling techniques,you transform a potential multi-day survival ordeal into hopefully just a few uncomfortable hours. And when those rescuers do arrive, whether it’s a search helicopter overhead or a farmer who saw your smoke signal, you’ll be ready: use mirrors or wave items to signal, have a fire going, etc., to guide them in.

Conclusion: Practical Preparedness in Every Flight

You don’t have to be a military pilot to benefit from SERE principles. By adapting Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape to general aviation, you become a more self-reliant, safety-conscious pilot. This isn’t about paranoia or expecting doom and gloom,it’s about confidence. There’s a certain peace of mind that comes from knowing you have the equipment, skills, and mindset to handle whatever comes your way.

As The Thrifty Pilot, I also want to stress that you can achieve a high level of preparedness without spending a fortune. Many of the best survival tools are inexpensive or even free: knowledge costs nothing (library books, YouTube tutorials on survival skills, FAA online courses), a basic survival kit can be put together with items from Walmart or your camping gear closet, and things like filing a flight plan or telling a friend your route are free. Even investing in a few key items like a PLB or quality multitool is a drop in the bucket compared to the price of avionics or a new headset,and which item would you rather have if you’re stuck on a mountainside? Prioritize wisely. (If you do have the budget, there are high-end ready-made kits put together by experts,for example, TacAero offers an Aviation Survival Kit developed with SERE instructors,but as one experienced bush pilot noted, you can put together a great kit yourself much more cheaply. It just takes a little research and creativity.)

In my experience in emergency management, the people who fare best in crises are those who acknowledged the possibility of trouble and prepared for it,without obsessing over it. They wore their seatbelts, kept their equipment in shape, ran an occasional drill in their head, and then went about life (or flying) with confidence. We as pilots can do the same. Pack that survival kit, review that emergency procedure, and then go enjoy the $100 hamburger flight knowing you’ve got contingency plans in your back pocket.

To recap, here’s a quick SERE-inspired preflight checklist you can mentally run through before each trip:

Survival Gear? Got my survival kit onboard and accessible (first aid, water, shelter, signals, etc.). Dressed for the weather. ELT functional, PLB packed if I have one.

Evasion Plan? Checked weather and NOTAMs; have alternates and outs for route. Briefed passengers on emergency procedures and survival gear locations. Keeping weight & balance in mind (don’t bury the gear).

Resistance (Mindset)? Committed to good decision-making today: I won’t succumb to get-there-itis or complacency. If something goes wrong, I’ll stay calm and stick to my training.

Escape/Rescue? Filed a flight plan or told someone my itinerary. Devices charged (phone, GPS, radio). Will use all available comms to call for help if needed.

Flying with a SERE mindset doesn’t make you any less of a fun-loving pilot,it makes you a smart and prepared pilot. You’ll likely never need your survival gear or emergency skills, and hopefully you never face a true survival scenario. But as the old saying goes: “Better to have it and not need it, than need it and not have it.” So pack smart, think ahead, and fly with the quiet confidence that you can handle whatever surprises aviation throws your way. That mindset, more than anything, is what will keep you safe. Stay thrifty, stay safe, and happy flying!

Sources:

FAA General Aviation Joint Steering Committee,General Aviation Survival (FAA Safety Briefing)

FAA Airman Education (Roger Storey, CAMI Survival Instructor),“Prepared for Anything”

AOPA Air Safety Institute,“Survive: Beyond the Forced Landing”

AOPA Pilot Magazine,TacAero Survival Kit and SERE training for backcountry pilots

Joint Base McGuire-Dix News,“CAP pilots credit survival to SERE training” (Rhode Island ditching, 2024)

Civil Aerospace Medical Institute,Basic Survival Skills for Aviation (FAA Survival Manual)

The Thrifty Pilot,“Top 10 Aviation Must-Haves Under $100” (on first aid kits and preparedness)

Comments